The rescue took six hours.

“Their faith was probably really strong to them because I don’t believe a lot of things they went through they would have been able to do without a higher power they had to trust,” Hester said.

And despite experiencing years of racial discrimination, the Pea Island surfman showed courage and professionalism by putting aside the bigotry they endured and rescuing the stranded passengers of the E.S. Newman – all of whom were white.

“They just knew it was the right thing to do,” Hester said. “And they did it.”

Etheridge died in 1900 at the age of 58. He is buried at the Pea Island Life Saving Station memorial on the grounds of the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island. Inside the aquarium, there is a spacious exhibit of paintings and drawings that tell the story of the Pea Island Life Saving Station.

“Richard Etheridge lead his all black crew, the surfmen of U.S. Lifesaving Station Pea Island, to accomplish the impossible on the night of October 11, 1896 as they rescued the passengers and crew of the E. S. Newman from a raging storm on the Atlantic Ocean,” said Kitty Dough, an historian with the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island who has done extensive research on the black surfmen. “From this heroic rescue and their tradition of service, these men a earned a unique role in the history of the Lifesaving Service which was to become the modern U.S. Coast Guard.”

“Having Richard Etheridge and members of his family buried in our Aquarium courtyard is a significant part of Outer Banks history at the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island,” Dough said. “The gravesite, monument placed by the U.S. Coast Guard, and series of historical paintings by James Melvin commemorating the lives and service of the Pea Island surfmen, honors the sacrifices, challenges and heroism of Richard Etheridge and his men for generations to come.”

In 1996, Richard Etheridge and the crew of the station were posthumously honored with a Gold Lifesaving Medal of Honor for their courage and service. The medal was obtained through the work of Kate Burkhart, a 15 year-old from Washington, N.C., who wrote an essay on the neglected history of the men and contacted Congress and President Bill Clinton to have the crew’s efforts and history acknowledged. And in 2012, a new Coast Guard cutter was named in honor of Etheridge.

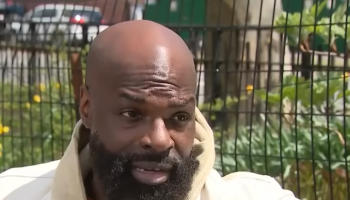

For Frank and Lynda Hester, operating their five-year-old museum and sharing stories about Etheridge and the Pea Island surfmen is a labor of love.

Since they both retired from the U.S Coast Guard, they would like to manage the museum full-time, but they need reliable volunteers to help out. They would also like to work more closely with the local schools and share the history of the black surfmen with public school students.

Frank Hester is happy to welcome people of all ethnic backgrounds into the museum, but he would also like the black community in Manteo to become more involved with the museum and embrace the community’s rich past. He is also quick to admit that it’s not easy to get young African Americans excited about history – even if it’s their own.

“It makes me want to try harder not to let those guys down and at the same time to blaze some trails and knock down some doors for the people coming up behind me,” said Hester, who is affectionately known by some in the community as “The Mayor.”

Hester’s family has a long history with the sea – and a distinguished history with the U.S. Coast Guard. Hester said many of his family members have owned their own boats for as long as he can remember and, as a family tradition, about 20 family members have proudly served in the U.S. Coast Guard since 1897 – 112 years of continuous service; 400 years of combined service. According to Hester, one of his ancestors, Wallace “Ralphie” Berry Jr., was the first black Coast Guard enlisted scuba diver.

Frank Hester served in the U.S. Coast Guard for 20 years and retired in 2001. His wife, Lynda, served for 22 years and retired in 2003. They are the only married family members who served in the U.S. Coast Guard together during their entire marriage. They have three daughters; ages 29, 25, and 20.

“Let’s take a walk,” Hester said as he pointed to a traffic circle just steps away from the museum.

Strolling across the street, Hester pointed to a life- size bronze statue depicting Etheridge holding the long oar of a rescue boat in his right hand. The statue rests atop a circular platform made of brick and cement. A bronze commemorative plaque with an inscription is mounted on a slab of granite on the grass in front of the platform.

“We’re proud of this statue,” said Hester, as he waved to every neighbor who drove by. “We’re proud of this North Carolina history. It means a lot to me. It should mean something special to everyone in this community.”

Black Life-Saving Crew in Outer Banks Remembered as Heroes for Daring Rescue at Sea was originally published on blackamericaweb.com